Table of Contents

- The Circular Economy Bike Business Model

- What Is A Circular Economy Bike Likely To Be Like?

- Aren’t Good Quality Products Already Lasting Forever?

- But What About Second Hand Bikes?

- Is This Just A Way For Companies To Get Extra Profit?

- Does This Model Work In Other Industries?

- Will This Model Work For Touring Bikes?

- Do You Think You Could Give Up Bike Ownership To Reduce Resource Consumption?

Islabikes made international headlines last month with their ambitious new Imagine Project. Their idea: to create bikes that last forever, therefore reducing the consumption of raw materials via their own circular economy.

…

I’ve been quite consumed recently upon researching the state of the environment – it’s terrifying. Even if the world was to switch to 100% renewable energy right now, we still aren’t addressing exactly what we do with that energy: that is, to extract more, build more, expand more and produce more for our ever growing population.

The embodied energy of everything we consume is often swept under the rug as complex manufacturing processes tend to hide overall emissions and waste. While exact energy numbers are hard to determine for objects like a bicycle; it’s safe to say our current rate of consumption is resulting in significant greenhouse gas emissions.

Coupling our consumption habits with increasing population growth, we’ve managed to double how much we dig out of the ground in just 35 years. In combination with greater levels of resource scarcity (the Earth’s resources are finite, after all), we should start preparing for some significant price increases on our raw materials.

But these things aren’t what underpins our need to consume excessively. It’s our economies.

Global progress is universally measured using GDP growth; and, the more the better. I’m simplifying this greatly, but most governments stimulate their economies in ways that optimise resource consumption, and at the same time our banking systems rely on constant growth. Large firms also require 3% growth annually in order to make profits in the aggregate. That means every 20 years we need to double the size of the global economy – double the bikes, double the cars and double the mining. Is it not madness that we’re aiming for infinite growth in a world with finite resources?

So what do we do about our environment? We use an economic system that is fundamentally flawed, demanding ever-increasing extraction, production and consumption.

Well, there are ways to achieve high levels of human development with very low levels of consumption. In fact, eight countries are currently meeting the minimum human development index (HDI) while also having ecological footprints below what is globally sustainable.

And here’s what bike companies can do.

The Circular Economy Bike Business Model

AKA Closed Loop, Circular Supply Chain

Here’s how it works: rather than a bike manufacturer absolving all responsibility of their product by selling it to you, bike companies would indefinitely own all of the resources used to construct their products.

Yep, you don’t get to own your bike. Instead, you’ll be renting the bike directly from the manufacturer. When you’re finished, the bike will get refurbished back at the factory who will then pass it on to the next person.

This is important in terms of corporate responsibility because it incentivises the use of less resources, encouraging manufacturers to design bikes that essentially last forever. The longer the bike is in service, the longer it can be rented out and the greater the return per unit.

It also allows for more efficient resource use in general, because should you not be riding the bike you’re renting, you would return it and somebody else would. It could also give you the freedom to switch between different styles of bike depending on your intended use. Optimise your bike for your commute, off-road tour, road bunch ride, mountain bike ride or round-the-world trip.

There’s more benefits too. You’ll get better service from the manufacturer as they have a greater interest in providing a product that lasts. They’ll also be able to afford to do a broader size range with smaller gaps between sizes; it’s almost like everybody gets a custom-sized bike. In addition, all of the components could be optimised around your body weight and riding style, meaning lighter parts for those who aren’t likely to damage them.

What Is A Circular Economy Bike Likely To Be Like?

We can look towards both the past, as well as the present to understand what a circular economy bike will be like. I think we can expect a mix of the proven bicycle technology from the last 100 years, as well as some of the more modern manufacturing techniques.

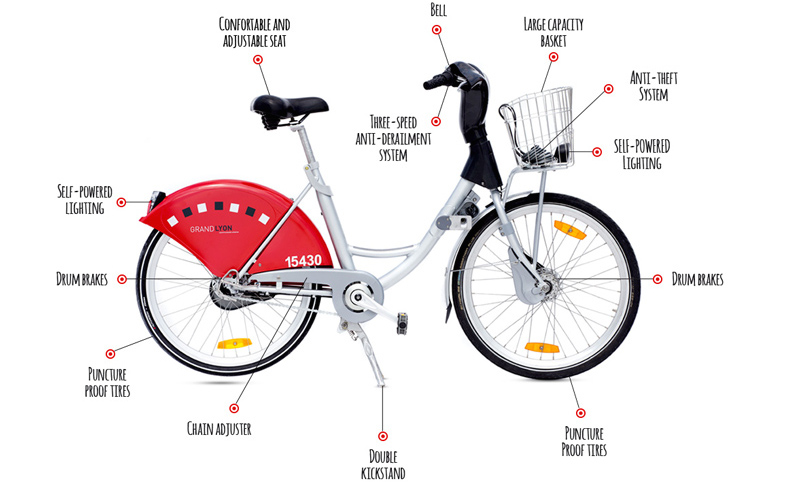

Current bike share models give us a good indication of a product designed for longevity as they need to be able to withstand adverse conditions, city streets and reckless behaviour. Another bike to look at for ideas is the modern touring bike – these are some of the only off-the-shelf bikes pieced together with long-term durability in mind.

You can expect these features on a long-lasting bike:

– Steel frames and forks

– Singlespeed drivetrains and internally geared hubs (enclosed)

– 8 speed rear derailleur drivetrains on the more performance oriented fleet

– Heavy duty aluminium rims

– Long lasting tyres (Schwalbe Marathon tyres are known to last 20,000km+)

– Coaster brakes

– Full length fenders and integrated dynamo lights

Islabikes are partnering with all kinds of component manufacturers currently to produce longer lasting parts for their Imagine Project. We can expect to see longer lasting consumables (tyres, tubes, chains, cassettes), as well as better sealed bearings and cabling. All other components will be designed around “fatigue limits” that are far greater than the wear and tear we put through our bikes.

Islabikes are making all of their business research ‘open source’, and being pioneers, their long-lasting components will be available to all other bike companies when they’re ready to adopt a circular economy business model.

Aren’t Good Quality Products Already Lasting Forever?

Some more conscious consumers will argue that when they purchase a bike, they do it with the intention of it lasting a lifetime. This will especially be the case with many touring bikes, as they’re typically built with durability in mind.

And this is where it gets interesting: circular economy bikes aren’t going to suit everybody.

If you are the kind of person who’s buying a product to last, you’re more likely to invest the money early and reap the long-term benefits of a quality product. You are actually taking responsibility for your consumption of resources, conscientiously or not.

Another example is with respect to high-performance athletes who are always going to rely on advances in technology in order to stay competitive. Circular economy design traits aren’t likely to offer anything of significant benefit.

In any case, for the majority of all sport, leisure and commuter cyclists – high-quality circular economy bikes have huge potential.

But What About Second Hand Bikes?

I hear you. The resources from second hand bikes have already been consumed, so you’re not consuming anything, right?

The thing is, the second hand market relies solely on the consumption of new resources in order to operate. Although you’re not the one consuming new items, you’re still taking part in a market which facilitates consumerism.

Of course, economic models will change over time, and buying well-designed second hand bikes/gear is currently the most ethical way to consume resources.

Is This Just A Way For Companies To Get Extra Profit?

One argument that has been proposed is that companies who already make long-lasting products (like Islabikes) just want to increase their margins by applying a new business model. I would counter that this is merely the point of a business, to create a plan that guarantees long-term growth.

And if said businesses can create a sustainable model that reduces the consumption of scarce resources, all while positively influencing the industry, is that not a great thing?

Does This Model Work In Other Industries?

Philips have been playing around with selling light output to business, rather than infrastructure. This has allowed them to both reduce energy costs and CO2 emissions, but more importantly – they have greater control over the recycling and repurposing of lighting components.

I think an even more interesting circular economy business model is by British car manufacturer, Riversimple. They are currently constructing hydrogen-electric cars that are capable of 250 miles-per-gallon! Like many circular economy products, you pay for the service and not the car. It will be interesting to see where this company goes in the future.

Will This Model Work For Touring Bikes?

Yes and no.

If you’re the kind of rider who spends very little time actually going bicycle touring, it will make sense to rent a touring bike directly from a manufacturer. This system will ensure that the fleet of touring bikes can spend the majority of their lives on the road, rather than in garages.

If you’re planning on buying a touring bike for life, it’s already quite possible to consume the one bike until you die. That’s pretty darn cool.

Thanks for the information about Isla bikes. I think it’s a good idea. However, it’ll be hard to implement in a bike industry that has got used to come up with new “improvements” each year, not compatible with the previous, and discontinuing wheel sizes that were the standard for the previous 30 years just to bring up a new size with a mere 1.25cm bigger radius.

A positive trend is the popularity of touring bikes, currently the only ones in this ever wider market segmentation that are made with reliability and long life exchangeable components in mind.

I don’t follow the reasoning against second hand bikes. Sure, many sell their old bikes to buy a new one. But many don’t. In kids bikes, the bike is just too small and they don’t need it any more. In adults, sometimes they just want to clear the shed, or they’ve realized only few of their bikes get actually used. The cycling population is not all made up of triathletes changing bikes every 2 years for marginal gains.

Reducing what I need (went down from too many bikes to “just” 3), and then going for used, is my personal strategy to reduce resources consumption.

I see the case for children bikes that have to change while they are growing up and people renting their touring bike although the problem with touring bikes is demand peaks during the summer and during the rest of the season it will be hard to rent them out.

Here in the Netherlands I see already something that is a bit like a renting model, the OV-fiets, see http://www.ns.nl/en/door-to-door/ov-fiets and that is quite successful. Also just read a report telling that 20% of the students that commute between Utrecht Central Station and the University (about 5 km) would be ready to bike instead of using the bus if the price was €1 per day while the bus is free.

I have my doubts if instead of owing “normal cycles” renting is more efficient, also the process of renting takes resources and typically people who rent or less careful then people owning their bike.

I assume the 1.25cm bigger wheel radius you’re referring to is 640B. If so, note that 650B was around a LONG time before the popular use of “26 inch” wheels. So the industry is “righting the wrongs” of Schwinn balloon cruisers. If you’re referring to “29er” (aka, 700c) that is also returning to much older wheel sizing. Thus in the end trying to get rid of a wheel size (26″).

I was indeed referring to 650B. In ISO numbers, 26” is 559, 650B is 584. If you

do the math, difference in diameter is 25mm, or 12.5mm in radius. The fact that

650B is an older standard says nothing about its suitability when the size was

just a NICHE French standard back when nearly each country had their own size

(650A, 650B & 650C, 700A, 700B & 700C, etc.).

It never reached the universal standard the 26” has achieved in the last decades. The Penny-farthing is a much OLDER standard, but nobody proposes that we should “right the wrong” and start running 52” wheels just because they came first.