Table of Contents

Weight is often the central focus for any discussion around bikes, components, and camping gear.

You’ll have noticed that I don’t emphasise weight very often on CyclingAbout, and that’s because it matters so much less than you think.

Don’t get me wrong, there are some great reasons to use lightweight gear, and I’ll discuss them all later in this article. But if you’re trying to reduce weight to go significantly faster, you’re probably barking up the wrong tree.

Today, we’ll find out the time penalty of each extra kilogram that you add to your bike or equipment. We’ll then compare these time penalties to other forms of cycling resistance.

Let’s start by putting weight into context.

Putting Weight Into Context

When you ride your bike up a hill, it’s not just your bike weight that you are hauling. You are pushing your body, clothes, shoes, water, food, pump, spare tube, and any luggage you might be carrying.

Your body weight makes up the majority of this load; it’s often more than 80% of the total.

While a bike that’s 10% lighter than another feels really impressive when you lift it up (eg. 9kg instead of 10kg), it often only reduces your total weight by 1% – which is now sounding much less impressive.

Shaving grams off bikes and equipment is often a very expensive pursuit too. One kilogram can be the difference between a $200 tent and a $600 tent, a $600 steel frame and a $1600 titanium frame, or a $3129 gravel bike and a $6199 gravel bike!

Additionally, lightweight products are sometimes much less durable. I find this with zips, waterproof fabrics, aluminium cassettes (and cassette bodies), tyres, and rims, in particular.

Alright, let’s find out how weight affects cycling speed.

Bike Speed Calculators

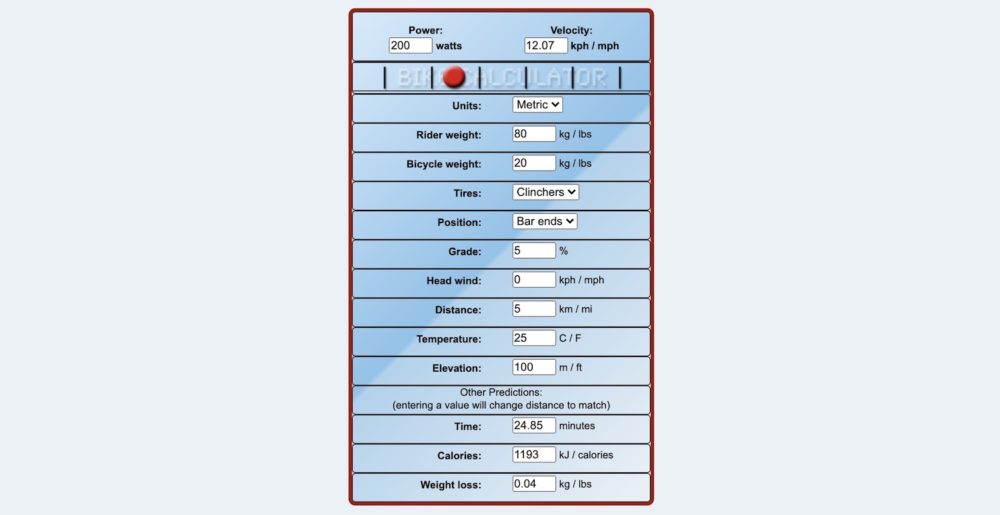

My journey to being less obsessed with weight began when I stumbled upon a website called Bike Calculator, which after filling in all of the parameters, could predict my cycling speed using a mathematical model.

I tested it out using my power output (200w), body weight (78kg), bike weight (15kg), and gear weight (various). I then created a simple 100km ride profile.

My Simple 100km Hilly Ride Profile:

» 5km up, 5km down (10x) on a 3.59%* gradient

» 1796m/5892ft* elevation gain

*The next section will explain why these numbers are oddly specific

I got time predictions on four different luggage weights so that I could work out the time, per extra kilogram, on my course.

Bike Calculator Provided The Following Time Predictions:

5kg Luggage: 4 hours, 14 minutes, 49 seconds

6kg Luggage: 4 hours, 16 minutes, 5 seconds – 76 seconds per extra kilogram

15kg Luggage: 4 hours, 27 minutes, 50 seconds – 78 seconds per extra kilogram (+13:01)

25kg Luggage: 4 hours, 41 minutes, 27 seconds – 80 seconds per extra kilogram (+26:48)

It turned out a kilogram should add between 76 and 80 seconds over 100km. And even if I reduced my power output by 30%, or set the parameters to a smaller rider (55kg) with a lower power output (120w), a kilogram was still only worth two minutes.

Considering that my route had quite a lot of climbing, a minute or two, over 4-5 hours of riding was significantly less than I had expected, so…

… I decided to conduct my own weight experiment!

Weight Testing on a Hilly Route

I rode my bike fitted with a power meter and two large panniers on a 15.37km (9.5mi) undulating route which offered 276m (905ft) of climbing. I pedalled along at 200-watts which was a power rate that I knew I could sustain over a full day of testing.

The route was well-sheltered, significantly reducing any hindrances from the wind. It was designed to mimic a day of cycling in the hills, whereby around 1800m (5905ft) of elevation would be gained over 100km.

I conducted two test runs with three different luggage weights: 5kg (11lb), 15kg (33lb), and 25kg (55lb).

Weight Testing Results

Carrying 5kg (11lb) on a 15.37km Circuit with 276m Climbing

Run 1: 39:55

Run 2: 39:25

Average: 39:40

Carrying 15kg (33lb) on a 15.37km Circuit with 276m Climbing

Run 1: 41:26

Run 2: 41:22

Average: 41:24 (+1:44 with 10kg extra)

Carrying 25kg (55lb) on a 15.37km Circuit with 276m Climbing

Run 1: 42:40

Run 2: 42:24

Average: 42:32 (+2:52 with 20kg extra)

Real-World Weight Testing vs. Mathematical Model

The numbers from my test are a little abstract, so let’s extrapolate them out to 100km to see how closely they match Bike Calculator’s prediction of 78 seconds per extra kilogram.

Extrapolated Data: 100km (62mi) with 1796m (5892ft) elevation gain

5kg Load: 4 hours, 18 minutes, 4 seconds

15kg Load: 4 hours, 29 minutes, 17 seconds – 67 seconds per extra kilogram (+11:13)

25kg Load: 4 hours, 36 minutes, 47 seconds – 56 seconds per extra kilogram (+18:43)

The added time averaged out to be a touch over a minute, suggesting that my perception of how weight affected cycling speed was, indeed, a bit off.

Bike Calculator was within just 1.5 and 4.5 minutes of my outdoor testing times, which I think is impressive considering the simple ride profile I created, only matched the distance and elevation gain. I’m sure the accuracy would improve further if I spent the time to make the gradients correct.

Weight & Flat Terrain

I later attempted an outdoor weight test on flat roads. It turned out that whether I carried 5kg or 25kg, I couldn’t find any significant difference in speed at 200-watts.

Feeling confused, I fed my parameters into Bike Calculator and it predicted that I should be just 10 seconds slower per extra kilogram over 100km.

I guess that explains why my speeds were so similar; weight really doesn’t matter on the flat.

Five Situations When Weight Actually Matters

The data and mathematical models suggest that a kilogram probably won’t slow you down that much. But there are a few instances when focussing on lightweight bikes and equipment is completely justified, in my opinion.

1. You do actually race (be honest).

The difference between winning and losing is sometimes measured in millimetres. One kilogram less is going to help here, and the benefits of that weight saving only increase the longer and more mountainous your race.

2. To improve bike handling and feel.

Heavy bikes don’t feel as snappy or responsive when accelerating or cornering, making them feel a little less inspiring to ride. They are also significantly less agile when you overload them with all your luggage.

3. To use a bike that isn’t designed to carry heavy loads.

If you’ve seen my video describing the differences between bikepacking and touring bikes, you’ll know that touring bikes are stiffer, and are built with a slew of overbuilt components (stronger wheels!) specifically to handle high luggage weights. But here’s the deal: if you can keep your luggage to a minimum, you can reliably travel on almost any bike – not just a touring bike.

4. To make lifting your bike and luggage easier.

There are many instances where you might need to carry your bike. For example, I’m often carrying my bike on hike-a-bike sections of trail, as well as up and down stairs in apartment blocks, hotels, and train stations.

5. To make flying cheaper.

A few extra kilograms can really add up when you get to the airport. Make sure to keep your bike light enough so that you don’t get caught out with crazy fees!

The Types of Resistance More Important Than Weight

Let’s talk about the factors that are often more important than weight when it comes to cycling speed.

Bike Calculator predicts that five extra kilograms adds 2.5% more time on my 100km hilly ride profile, and it’s just 0.4% more time on a flat profile.

(Power = 200w, body weight = 78kg, bike weight = 15kg, gear weight = 0kg)

We can compare these time percentages to the two other main forms of cycling resistance – rolling and aerodynamic resistance.

1. Rolling Resistance

If I fit some of the slowest-rolling touring tyres (Vittoria Randonneur) to my bike instead of the fastest-rolling ones (Schwalbe Almotion), my 100km hilly route would require 12.0% more time to complete.

In this case, rolling resistance is almost 5x more significant than adding 5kg to my bike on the hilly profile (12/2.5=4.8), and 17x more significant on the flat profile (6.7/0.4=16.8).

That said, these numbers are particularly big because I’m comparing the fastest tyres with some of the slowest. But even if we compare tyres closer to the middle of this list (Marathon Greenguard vs Marathon Mondial), the rolling resistance still works out to be more significant than the extra 5kg of weight (+3.7% time on the hilly profile).

You can see my tyre rolling resistance article HERE.

2. Aerodynamic Resistance

Through my aerodynamic testing on a flat velodrome, I found between 6.4% to 7.9% extra ride time was required to cover 100km when using panniers instead of bikepacking bags.

This means that a change in luggage set up on a flat ride could be 16-20x more significant in terms of time than if I added 5kg of extra luggage to my bike (7.9/0.4=19.8).

You can read my list of aero savings for bikepacking HERE and see my velodrome test HERE.

Summary

The data is quite clear; bike weight is not as important as you think!

My real-world testing, along with the numbers from the mathematical models, suggests that a kilogram extra weight will likely add one or two minutes on a hilly 100km bike ride. And on a flat route, a kilogram is likely worth 10 or 20 seconds over 100km.

This is worth thinking about if you find yourself obsessing over bike and gear weight.

Perhaps, you can use this information to save $1000-2000 by choosing a steel bike rather than titanium. Or when your ultralight gear wears out, maybe you could replace it with something more durable. You could even pack a thicker, more comfortable sleeping pad to get a night of better sleep!