In theory, a carbon handlebar should be more compliant because it allows for more flex than aluminum. Subjectively you can feel it, but I also wanted to find out what my vibration measurements would show.

So, today we’ll be testing two aluminum and two carbon handlebars. And the results may surprise you!

Carbon vs Aluminium Handlebars

Carbon handlebars are unique in that they can be made stiff in some directions of force but flexible in others. They can also be constructed ultra-lightweight – you can find many drop bars that are well under 200 grams in weight.

If you’re planning on using carbon handlebars, there’s just one thing to know: you should be super careful with installation. A stem can easily crush a carbon handlebar at the point where it intersects. You can prevent this failure mode by simply not exceeding the torque limits set by the manufacturer; you’ll just need a torque wrench for fastening everything up.

If this is too much for you, you might just want to use an aluminium handlebar. But do you really want to sacrifice this comfort?

I had to find out if this was indeed the case.

The Handlebars On Test

In this field test, I will be measuring the vibrations of a Spank Wing 12 Vibrocore aluminium handlebar. This bar has some special foam inside, which is intended to minimise road vibrations.

I also have a bike fitter favourite, a Zipp Service Course SL-70 Ergo handlebar. This aluminium bar is well-known for its stiffness, shape, and weight.

We also have some unique carbon handlebar contenders…

First, it’s a Coefficient Wave handlebar that has a very distinctive shape. For some reviewers, it also offers fantastic damping properties when riding in the drops.

There is also a more well-renowned carbon handlebar in the test field, a Ritchey WCS VentureMax. This bar has uniquely shaped flared drops and some very comfortable flat bar tops.

Key Differences Between The Handlebars

The Spank Wing 12 handlebar was in a different width – it was 440mm wide while the rest were 420mm.

Two of the tested handlebars (Spank and Ritchey) have a significant flare (12 and 24 degrees) while Zipp has only 4 degrees of flare and Wave even less than that.

Zipp and Coefficient also have ovalized tops while Spank and Ritchey have very pronounced flat tops areas, which could influence the results recorded when riding on the bar tops.

My Subjective Experience With These Handlebars

Before I will talk about the vibration test results, I want to give you some subjective observations.

First, there was a huge perceptible difference when trying to flex the carbon handlebar vs aluminium one. The stiffness of the aluminium handlebars that I tested was substantial, and I was trying very hard to make them bend at all.

In comparison, the carbon bars were bending easily – the Wave seemed slightly more flexy than the Ritchey handlebar. The flex was most apparent when riding in the drops, but in the hoods, it was also very much perceptible.

Then there are the famous road-buzz-damping properties of carbon. To be honest, I did not notice this at all. I also could not feel the Vibrocore foam doing its work inside the aluminium Spank handlebar.

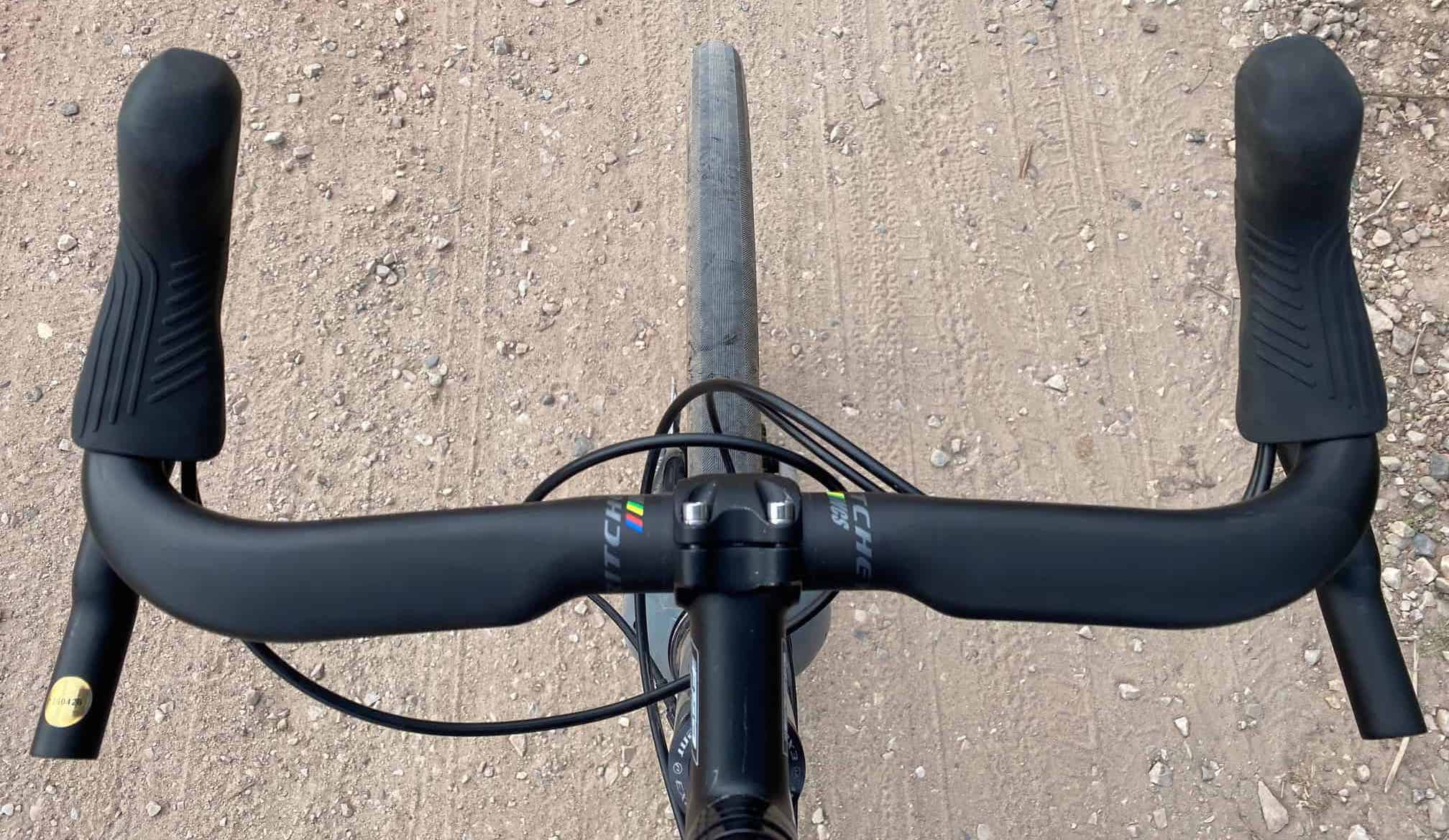

The Test Bike

To make the difference best bars most visible, I used my Jamis Renegade benchmark bike with a rigid Open U-turn carbon fork and 90mm rigid stem (with 25mm spacers below).

The front tire was a Rene Herse Barlow Pass 38mm that was inflated to 40 psi. The rear tire was another Rene Herse Barlow Pass but this one was inflated to 30 psi. I chose a lower pressure in combination with a Redshift ShockStop suspension seatpost and SQlab 612 saddle to make sure that the rear of the bike does not influence the front-end vibration measurements.

I did not wrap the handlebars with bar tape because again, I did not want to influence the results. I was using my regular Giro gloves.

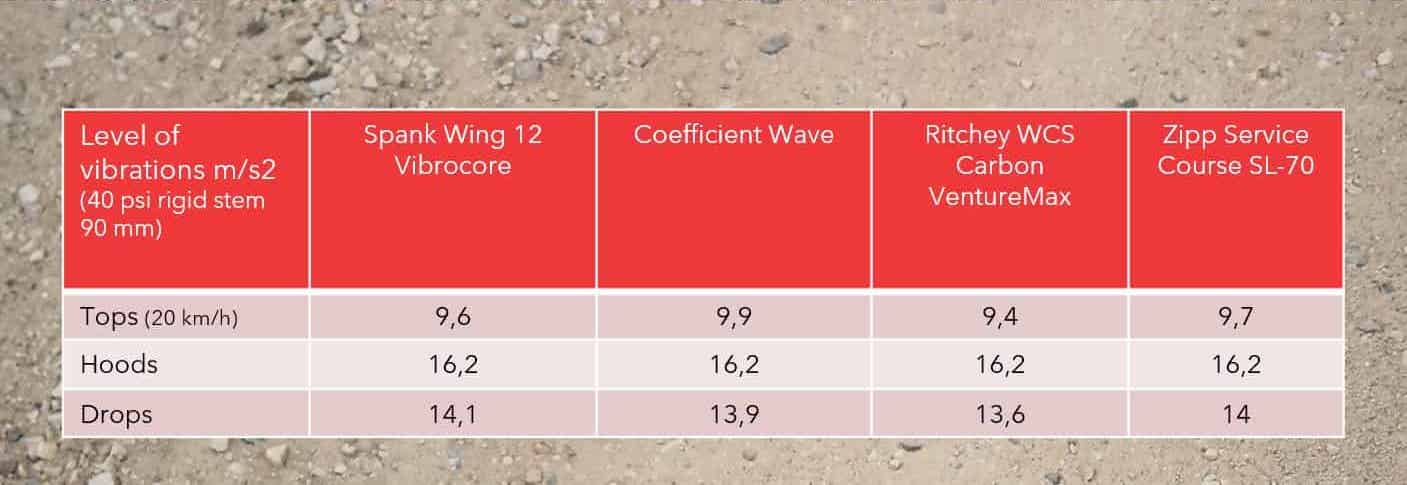

As usual, the vibrations were first measured while riding in the hoods. But I also added bar top and drop measurements. The bar tops measurement on the fast gravel road was actually measured at 20km/h (not 35km/h), as I wanted to try to try to replicate my “cruise mode” when I actually do use the bar tops.

Vibration Test Results

You can see my vibration measurement procedure & outdoor test courses HERE.

Let’s start with the bumpy forest trail test.

The most striking thing when looking at those results is that there is only a slight difference in terms of vibrations between aluminum and carbon handlebars. I was expecting something like a 10% difference in vibration attenuation, but in reality, it was more like 5-6% in the best-case scenarios.

When riding in the hoods there were some differences between handlebars, but not between carbon and aluminum. The more flat and flared handlebars performed slightly better (Spank and Ritchey), suggesting that these shapes could be beneficial in terms of absorbing big bumps.

On the bumpy forest trail, the Ritchey was the best in the drops. But again, we are talking about a 6% difference between the best and the worst handlebar.

What surprised me most were the differences when riding on the bar tops. When you ride up top, you put less weight on the front wheel and your arms are able to move more freely. But the taller the bar tops (Wave handlebar), the less weight you put on your front wheel, and this results in a more bouncy front end (the Wave had 9% more vibrations than the Spank).

Objectively, I could measure more vibrations at the bar tops, but I must say, in this position, my arms felt more relaxed, so the vibrations did not seem to translate into more tiredness.

Moving on to the fast gravel road.

I was surprised that there was zero difference between the handlebars when riding in the hoods. Due to a very high level of measured vibrations, I had to do five test runs for each handlebar (it’s usually three). And even when I calculated the average of all five runs, the handlebars presented very similar levels of vibrations.

Fortunately, the drops brought more variation. Both of the carbon handlebars performed better but only by a slight margin (1-3%).

When riding in the bar tops at 20km/h, the Ritchey was again the best (it was 5% better than the worst). But the Spank handlebar was second in this test, which might prove that Vibrocore is indeed doing something (it was 3% better than the worst).

A more probable explanation is that the flat bar top shape is more beneficial because your upper body weight can be more evenly distributed across your hands.

Again, the Wave handlebar with its taller bar tops was the worst performer here. But I believe that your arms are the most relaxed on the Wave bar tops, so the higher levels of vibrations likely won’t translate into more fatigue.

Summary

With such small differences in vibration attenuation between these handlebars, these results show that you should focus much more on the ergonomics of the handlebar than everything else.

In this test, the Ritchey WCS Carbon VentureMax handlebar did offer slightly more compliance than the rest. The improvements were found primarily in the drops, but on the bar tops too. However, it’s not even close to the levels you would guess just by riding them.

Overall, you shouldn’t be too concerned about your gravel handlebar material. The level of compliance offered by the much cheaper aluminum handlebars is very similar to carbon, and an added advantage is that you will not need to worry about damaging the carbon either.

You can support the CyclingAbout Comfort Lab by purchasing Ritchey WCS Carbon Venturemax handlebars on Amazon. Simply click HERE for 420mm width, HERE for 440mm width, and HERE for 460mm width – and a small commission will come our way.